Created by: Heather M. Truog, OTD, OTR/L, PYT

capstone project for post-professional doctoral program

University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences

SEXUAL ASSAULT &

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD)

Last updated: September, 2019

KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

The rate of sexual violence perpetrated against women and children in the United States is alarmingly high.

-

There are strong correlations between the experience of sexual trauma and the incidence of physical symptoms manifesting as pelvic floor dysfunction, as well as complex mental disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which have a wide range of impact upon participation in daily occupations and perceived quality of life.

-

Females manifest PTSD differently as a result of the way their brains process the traumatic experience, and as an outcome represent a 2x higher rate of diagnosis than men.

-

The literature calls for holistic and integrated treatment interventions that address all aspects of an individual’s presentation across a biopsychosocial landscape.

-

Occupational therapists are uniquely qualified to provide a client-centered and integrated approach to intervention through examining and addressing manifestations of mental and physical dysfunctions within the occupational profile.

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

Within the United States, the occurrence of sexual violence exists at an alarming rate. According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network ([RAINN], 2018), a sexual assault takes place every 98 seconds. With one out of every six women in the United States falling victim to an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime (14.8% completed; 2.8% attempted; RAINN, 2018). While rape is more commonly perpetrated against women, this act is not a phenomenon entirely isolated to females. One in thirty-three (nearly 3%) of American men has experienced an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime (RAINN, 2018). Between the time frame of 2009 and 2019, Child Protective Services agencies substantiated that over 60,000 children a year were victimized by sexual abuse (RAINN, 2018).

The statistics pertaining to sexual abuse and assault in this country are deeply concerning. Particularly when the evidence clearly articulates that such traumas have complex and long-term impacts on mental, physical, and psycho-emotional health. Manifestations of complex pain and pelvic floor dysfunction following trauma can inhibit proper functioning of basic activities of daily living (e.g., bowel and bladder functions, engagement in sexual activity) while the experiences of trauma can manifest in the form of more serious mental health diagnosis (e.g., depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder). Experienced as uniquely individualized or combined manifestations of symptomology following such a trauma implies a significant impact upon the lived experience and perceived quality of life of the woman in question.

PSYCHOSOCIAL AND SOCIOCULTURAL IMPACT

The Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network ([RAINN], 2018) lists multiple potential effects of sexual violence including: depression, flashbacks, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), self-harming, substance abuse, dissociation, eating disorders, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pregnancy, sleep disorders, and suicidal ideation. Of these potential complications, PTSD has been explored in the literature with increased attention to the relation of sexual assault.

A traumatic experience, or event that is characterized by direct or indirect exposure to a potentially serious injury, the threat of death or sexual violation may lead to the onset of PTSD (Kim, Amidfar, & Won, 2018). The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5, (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) defines PTSD as comprised of four clusters of symptoms including (APA, 2017, p. ES-3):

-

Intrusive and recurrent memories of the trauma

-

Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli

-

Numbing and/or negative changes in mood or cognitions pertaining to the trauma, and

-

Changes in reactivity and arousal

Presentations of the disorder can manifest in a relatively mild form or can be entirely debilitating (APA, 2017). The APA (2010) indicates that “although 50-90% of the population is exposed to traumatic events during their lifetimes, most exposed individuals do not develop PTSD” (p. 9, italics added for effect). Within the United States, the prevalence of this diagnosis is approximated to affect 8% of the general population (Ramikie & Ressler, 2018).

Even though men are exposed to traumatic events at a statistically greater rate over the lifespan, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in females is two-fold that of males (Ney, Matthews, Bruno, & Felmingham, 2018). Additionally, females have been found to experience greater severity and chronicity of symptoms related to PTSD, with strong evidence suggesting that the type of trauma one is exposed to has a significant impact on pathology (Ramikie & Ressler, 2018). Ramikie and Ressler (2018) further indicate that while “males are more likely to experience non-assaultive trauma such as accidents, females are more likely to experience interpersonal trauma, such as sexual violence” (p. 876). Given the elevated rate at while women in the U.S. experience sexual violence compared with men (RAINN, 2019), it is not surprising that the prevalence of PTSD in women is similarly elevated by comparison.

Evidence suggests that the unique interplay of the cyclic nature of the female reproductive system with the hypothalamic—pituitary—adrenal axis (HPA axis) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) increases the complexity of PTSD symptomology among women, with an increased window of vulnerability between the time frame of puberty and menopause (Kim, Amidfar, & Won, 2018; Ramikie & Ressler, 2018). Studies also indicate that female-specific hormones impact the neural processing of fear within areas of the brain such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Ramikie & Ressler, 2018). Additionally, Inslicht and colleagues (2013) found that women with PTSD display a higher propensity for fear conditioning as a result of experienced trauma associated with elevated states of arousal. This propensity may result in what is a seemingly innocuous stimulus triggering a conditioned fear response despite no danger being immediately present (Inslicht et al., 2013).

Understanding how PTSD is processed in the female brain is just as important as understanding and identifying the symptoms and sequelae of sexual trauma and PTSD presentation when attempting to provide best practice care. Recognizing and understanding trauma presentation in the form of intrapersonal and interpersonal behaviors, attitudes, symptomology, and lifestyle choices may be the difference in providing best care service application and service coordination for the healthcare professional working in this domain of healthcare.

BARRIERS TO PROPER INTERVENTION:

The largest barrier in effectively managing physical and psychosocial symptoms exists in the proper identification of individuals who have suffered such trauma and have manifested subsequent symptomology. In relation to surviving sexual violence, a victim may be unwilling or unable to come forward to report her attack due to fear of retaliation, lack of trust in the justice system, cultural stigma, shame, fear of sustaining further injury, protecting the perpetrator, and lack of personal value (RAINN, 2018) and therefore would go un-documented within the justice and healthcare systems. Only about 23% of rapes are reported to the justice system (RAINN, 2018). With current statistics indicating that of the victims under the age of 18, 34% of victims of sexual assault and rape are under the age of 12, and 66% of victims are between the ages of 12-17 (RAINN, 2018), it is even greater in likelihood to speculate that these younger survivors of childhood trauma will go without reporting or healthcare seeking. Research from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network suggests that one in four girls and one in six boys experience sexual abuse in one form or another before the age of 18, with many of such cases going unreported, kept in secret (Florian, 2018).

Some women with a history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) were found to be less likely to regularly access routine or preventative healthcare services, and may altogether prefer to avoid the clinical healthcare setting, while other women have been found to seek out medical services for grossly unexplained physical symptoms that are typically classified as somatic complaints (Florian, 2018). The author further indicates that women with histories of CSA that access healthcare specific to their reproductive systems may willingly omit their past trauma history from intake information, relegating these situations and experiences to a past they would prefer to forget (Florian, 2018). Many women may not be aware that the pain or dysfunction of their pelvic floor or reproductive anatomy is linked in some way their experiences of CSA, reinforcing an unwillingness to divulge information, and therefore making it more complicated to draw associations between the symptoms and experience, limiting access to needed care.

Stories of why women are keeping silent...

How we as a community can support them better...

University of Washington School of Medicine (2018)

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ROLE OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY IN ADDRESSING TRAUMA RECOVERY

THE OT'S ROLE WITHIN THE INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM

The AOTA posits that “occupational therapy practitioners are qualified mental health professionals who assist people experiencing barriers to engage in meaningful roles and occupations to increase their participation, health, and wellness” (2015, p. 1). Integration of the various theory of practice and frame of references options specific to occupational therapy increases the opportunity to meet the client’s intervention needs by establishing the best fit within applicable scenarios. This is where occupational therapists exhibit a unique skillset to perform best-practice interventions.

Occupational therapists (OTs) have the integrative training to address various women’s health conditions that may result following trauma from a holistic and client-centered perspective. Given the specific educational backgrounds that OTs possess in addressing client, activity, and environmental analysis and interconnections, combined with the depth of understanding they possess in neuroscience, anatomy, physiology, and mental health, they should be considered an integral component of the trauma recovery process (AOTA, 2015). Returning a client to the ability to engage in meaningful roles and daily activities to regain health, wellbeing, and perceived quality of life is the primary objective of the occupational therapist.

The scope of intervention that the OT is ethically able to provide in such a scenario is directly related to the extent of their specialized training. For those OTs who are specifically trained in pelvic floor rehabilitation, an internal and/or external examination of the biomechanical components of the client's presentation may be warranted if the appropriate request of services has been obtained from the referring provider. If performing pelvic floor evaluation and intervention is not within the specialized scope of practice of the therapist, the OT remains an integral member of the interdisciplinary team to address aspects of the occupational profile beyond the biomechanical limitations of the pelvic floor, and are capable of screening for and requesting referrals to the appropriate healthcare specialists needed to collaborate in best-care to address identified needs.

Understanding how the survivor of sexual trauma may present with symptoms of PFD and PTSD, and the intricate correlation between the two, is essential to providing best-practice care. This is particularly true when considering the bidirectional channel of referral sources that may be required to achieve optimal outcomes for the patient. Whether the individual presents to the mental health provider seeking treatment for the presentation of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, or potentially to the urogynecological expert for a reprieve from pelvic floor dysfunction manifestations, crossing these channels to achieve encompassed care for both mental and physical presentations is pivotal.

Postma and colleagues (2013) draw a correlation between their data findings and the need to “develop integral trauma exposure treatments that include (physical or psychological) treatment strategies for sexual dysfunction and/or pelvic floor dysfunction rather than separate modules following after one another” (p. 1985). As the OT practitioner is uniquely qualified to address elements of both the biomechanical components of PFD through manual therapy and mobilization techniques, while simultaneously equipped to address the psychological barriers associated with anxiety, depression, and PTSD through use of psychotherapeutic and cognitive behavioral frames of reference, the women's health specialized OT is a potentially invaluable member of the interdisciplinary team. As the experience of sexual trauma has a significant effect on an individual's ability to participate in daily occupations, the OT practitioner can design intervention strategies that are uniquely in the language of the occupational perspective, addressing the physical and mental presentations as elements of the daily lived experiences.

SEXUAL ASSAULT AND PTSD'S IMPACT ON THE OCCUPATIONAL PROFILE

The potential for the presentation of physical, mental, and psychoemotional sequelae following a sexual trauma may equally manifest as dysfunctions throughout the individual's occupational profile. Within the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework (OTPF), critical areas of concern for occupational performance are in ADL functions (e.g., toileting, toileting hygiene, and sexual activity), IADL functions (e.g., health management and maintenance), rest and sleep, engagement in social participation, and engagement in play or leisure tasks (AOTA, 2014) resulting from manifestations of both physical and mental conditions.

The following table (Table 1) describes the ways in which sexual assault complicated by PTSD presentation can have the potential for broad impact upon an individual’s occupational profile. The information in Table 1 representing Category and Description of occupation is directly quoted from the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process [3rd edition] (AOTA, 2014, p. S19-S21), the table is further adapted to include diagnosis-specific interpretation of relevance.

Table 1. (link to PDF)

UNDERSTANDING SEXUAL ASSAULT AND ITS CORRELATION WITH PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION:

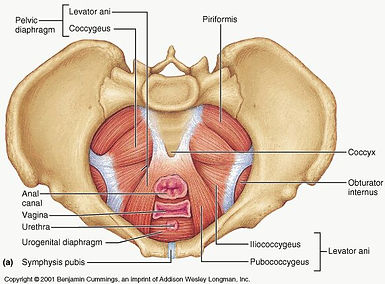

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) implies impaired function of basic activities of daily living such as toileting and sexual activity. Research indicates that there are strong correlations between sexual trauma and PFD. Postma and colleagues (2013) found in a cross-sectional study that rape victims had a 2.4 times greater prevalence of sexual dysfunction (i.e., lubrication and pain) and a 2.7 times higher incidence of PFD (i.e., provoked vulvodynia, stress, lower urinary tract symptoms, and irritable bowel syndrome symptoms) than controls. With 33.7% of the rape victims found to have hypertonicity of the pelvic floor muscles versus 12.4% of the control group (Postma, Bicanic, van der Vaart, & Laan, 2013).

Carreiro and colleagues (2016) articulate that women with a history of sexual abuse occurring in childhood or adolescents are reported to experience high rates of sexual dysfunction. While not all, many have the potential to develop psychological and sexual problems including dyspareunia, difficulty achieving arousal and orgasm, and a lack of interest in sexuality (Carreiro et al., 2016). While others may manifest complaints including dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, and chronic pelvic pain that have been found to be late sequelae of sexual abuse that may not be directly correlated to the initial source of abuse by healthcare providers until many years following the event (Carreiro et al., 2016). The cross-sectional research study that was conducted by Carreiro and colleagues (2016) indicated that beyond the increased relationship between PFD and sexual abuse, of the greater than 2000 individuals’ data that was obtained from, health-related quality of life scores were found to be significantly lower among the participants with a history of sexual abuse.

Experiences of sexual trauma have further implications on the individual's ability to effectively manage and maintain healthy behaviors. In a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Abajobir and colleagues (2017) findings indicated that sustained childhood sexual abuse (CSA) in females is associated with a greater risk of risky sexual behaviors (RBSs) such as multiple numbers of sexual partners, increased frequency of sexual engagement, and incorrect or inconsistent use of contraception. These high-risk behaviors represent the potential to develop into greater healthcare complications which may further progress to poor reproductive health outcomes such as infertility, pelvic inflammatory diseases such and STIs including HIV (Abajobir et al., 2017). Abajobir and colleagues (2017) posit that screening for RSBs and adequately offering access to integrative healthcare interventions that address the underlying biopsychosocial risk factors for RSBs is essential for healthcare providers to alleviate the greater public health concerns associated with RSBs.

THE ROLE OF THE PELVIC REHABILITATION THERAPIST:

The primary function of the pelvic floor rehabilitation practitioner, whether licensed as an occupational therapist or physical therapist, is to assess and treat the structural integrity of the pelvic floor musculature, surrounding musculature, soft tissues, viscera, and joints in both male and females patients. Pelvic rehabilitation therapists help to restore urinary, bowel, and sexual functions that involve dysfunctions of these soft tissues and bony landmarks (Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, 2019).

For the female population, comprehensive evaluation by a pelvic rehabilitation therapist includes an internal and external vaginal and/or rectal assessment to determine the individual’s pelvic floor strength, control, coordination, and flexibility. Internal assessment involves the therapist manually palpating with use of a gloved finger the structures of the pelvic floor musculature and surrounding soft tissues. Generally, this is completed in a methodical fashion using a ‘pelvic clock’ model to systematically identify and assess various landmarks and muscular structures. Treatment interventions may include manual therapy mobilization techniques of soft tissues, viscera, and joints; use of Biofeedback devices to engage control and coordination of pelvic floor musculature; verbally or tactically instructed therapeutic exercises and neuromuscular reeducation to restore muscular function and control, strength, or flexibility; bladder/bowel and dietary education to promote optimal functioning and healing; habituation retraining; or modalities to assist with pain, muscle strength, and/or urgency (Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute, 2019).

photo citation: www.praiowa.com

Despite the clinical nature of the assessment and intervention techniques, some women may find the internal components of treatment triggering to previous traumatic experiences. As the pelvic therapist is working in an intimate region of the patient’s anatomy, it is particularly important to possess knowledge and skills for trauma-sensitive practice delivery. Just as multiple researchers have urged adherence to trauma-aware and trauma-sensitive protocols to be followed for those healthcare professionals working in reproductive health (Carreiro et al., 2016; Florian, 2018; Gottfried, Lev-Wiesel, Hallak, & Lang-Franco, 2015; Postma, Bicanic, van der Vaart, & Laan, 2013; Ryan et al., 2016), it is equally important for therapists working in practice domains that involve internal pelvic floor assessment and intervention to be cautious and respectful of the significant correlation between pelvic floor dysfunction and post-traumatic stress. The patient presenting for treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction may have unresolved or unprocessed memories, feelings, or experiences of traumatization. Equally, patients who have sought clinical psychotherapy interventions for the mental and emotional aspects of sexual trauma may have unprocessed physical triggers of trauma within their pelvic floor anatomy (Postma, Bicanic, van der Vaart, & Laan, 2013).

SEXUAL TRAUMA AND POLYVAGAL THEORY

The unique nature of processing sexual trauma...

Dr. Peter A. Levine holds doctorate degrees in both Medical Biophysics and in Psychology. He spent 35 years studying stress and trauma and has contributed to numerous scientific and popular publications. Dr. Levine was a stress consultant for NASA on the development of the space shuttle project, as well as a member of the Institute of World Affairs Task Force of Psychologists for Social Responsibility in developing responses to large-scale disasters and ethnopolitical warfare. In 2010, Dr. Levine received the Life Time Achievement award from the United States Association for Body Psychotherapy (USABP).

Here he discusses the unique nature of sexual trauma, and the delicate balance of the body physically processing pleasure and pain combined with how the brain's internal systems interfere with the individual's experience, causing a conditioned traumatic response.

Somatic Experiencing Trauma Institute (2011)

The cyclic nature of shame and repression that Dr. Levine speaks of in the above video interview is a recurrent theme for many women who verbalize accounts of their sexual trauma experiences. For some, the experience of their trauma may be amplified by the shame and self-blaming that result from “not fighting back”. Many women who have experienced trauma with this behavioral outcome may benefit from applying knowledge of Polyvagal Theory.

The work of Dr. Steven Porges and his contributions to the advancements in Polyvagal Theory (PVT) may help to build a deeper understanding, association, and opportunities for mechanisms for intervention when moving forward in the treatment of this population. PVT outlines the functions of three distinct neural platforms as they respond to a perceived risk (i.e., safety, danger, or life threat), which then trigger a complex neurological response that is linked to behaviors of social communication, defensive strategy of mobilization, or defensive immobilization (Porges, 1995, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2007, 2009, 2011).

Trauma-informed pelvic floor therapists, as well as occupational therapists working with PTSD populations across a range of traumatic origins, should be aware of how PVT may impact the presentation and outcomes of their client populations.

A new perspective on trauma...

Applying Polyvagal Theory to sexual trauma...

NICABM (2011)

NICABM (2017)

The research of Dr. Stephen Porges intersects psychology, neuroscience, and evolutionary biology. Through his development of the Polyvagal Theory (PVT), Porges is discovering how the autonomic nervous system (ANS) controls the reactions and behaviors of individuals affected by a variety of traumatic experiences, including sexual assault and partner violence.

In this video, Dr. Porges discusses the way in which PVT may be applied to the experiences of sexual trauma and shares insight to understanding the way in which the "freeze response" represents a protective mechanism of the human brain.

ADDRESSING PTSD FROM THE OCCUPATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Within the AOTA’s Societal Statement on Stress, Trauma, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (AOTA, 2018), the contributors posit that:

“The education of occupational therapy practitioners includes an emphasis on mental health and the training necessary to work with individuals of all ages who are experiencing stress, trauma, and other mental health conditions. Practitioners help clients identify therapeutic needs, goals, and activities and strategies supporting participation, resiliency, and the recovery process. As part of the occupational therapy intervention process, a variety of activities, coping techniques, and environmental supports are identified that may be used to help prevent, manage, or release the symptoms of stress, trauma, and posttraumatic stress, supporting safety, stabilization, and participation” (p. 1).

While much of the research conducted by occupational therapists in the realm of PTSD recovery has pertained directly to service member and activity duty combat trauma survivors, occupational therapists Gerney and Muffly (2015) speak specifically to the role of the occupational therapy profession in addressing rape trauma syndrome (RST). They outline the correlation to the hyperarousal of the sensory system that occurs in many individuals following such an experience of trauma (Gerney & Muffly, 2015). These therapists further indicate that, as many PTSD treatment methods may be ineffective when addressing trauma specific to rape, addressing the sensory components directly through alternative methods may be integral for successful treatment of the symptoms experienced (Gerney & Muffly, 2015). Intricate knowledge of the client's sensory system may enable the OT practitioner to approach the issues of flashbacks and flooding sensory information experienced by the client in a uniquely client-centered way when addressing the occupational components of recovery.

The AOTA does not have a specific clinical practice guideline for addressing sexual traumas, nor pelvic floor dysfunction; however, the OT practice domain as outlined in the OTPF implies that application of occupational interventions for this population is within the scope of practice of occupational therapists. The AOTA does, however, have an established Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Adults with Serious Mental Illness (AOTA, 2012) which can be applied to the components of the intervention that target PTSD symptom presentation as a result of sexual trauma.

Even though PTSD is not explicitly listed as a primary mental illness as outlined within the practice guidelines, it is noted that “serious mental illness may co-occur with other conditions, such as substance dependence, trauma, and/or personality disorder. In such cases the serious mental illness should not be treated in isolation; instead, the occupational therapist should use a holistic and comprehensive approach that considers other relevant practice models” (AOTA, 2012, p. 7). As major depression and panic disorder are identified to be inclusive of serious mental illness as outlined in the practice guideline and known to be potential comorbid complications of sexual trauma, it is important and to take a comprehensive approach to mental health intervention when addressing complex presentations of pelvic floor dysfunction that may be originated by sexual abuse or assault.

As articulated in the Occupational Therapy Practice Guidelines for Adults with Serious Mental Illness, “part of the occupational therapy process is to develop an intervention plan that considers the client’s goals, values, and beliefs; the client’s health and well-being; the client performance skills and performance patterns; collective influence of the context, environment, activity demands, and client factors on the client’s performance; and the context of service delivery in which the intervention is provided” (AOTA, 2012, p. 16). After identifying target goals that are made in collaboration with the client, the therapist then must determine an appropriate approach to intervention.

APPLYING A BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL

As articulated in the previous sections of OT For Women's Health, the occupational therapist has a unique educational background in facilitating both physical modalities of intervention as well as psychosocial aspects of intervention, they are uniquely situated to deliver patient-centered care from a biopsychosocial model. This model allows the therapist to consider the diverse factors of biological, psychological, and sociological influences when creating an intervention plan (Gentry, Snyder, Barstow, & Hamson-Utley, 2018). Each of these dimensions of care has been shown to have a direct impact on the intermediate and final rehabilitation outcomes (Gentry, Snyder, Barstow, & Hamson-Utley, 2018). Gentry and colleagues’ (2018) adapted the Biopsychosocial Model for use in the OT practice addresses the needs of client across the continuum of care, incorporating seven key elements:

-

Characteristics of the condition (previously termed injury characteristics)

-

Sociodemographic variables that impact

-

Biological variables

-

Psychological variables, and

-

Social-contextual variables (which reciprocally interact with each other), to impact

-

Intermediate, and

-

Rehabilitative outcomes

The following presentations depict Case Vignette 3 - Tonya, which provides a client-specific scenario utilized to provide context to the completion of the biopsychosocial chart (as outlined in the previous section covering Endometriosis & Chronic Pelvic Pain, Figure 1), elaborated within the secondary presentation on Applying the Biopsychosocial Model as adapted for occupational therapy.

Case Vignette 3 - Tonya

Applying the Adapted Biopsychosocial Model

CONSIDERING OTHER MODELS IN ACTION

As stated and reiterated in prior sections, the Biopsychosocial Model as adapted for OT is only one example of an applicable model of care to address the client's intervention needs. Many other well established occupationally focused models of care can be applied to the intervention process and may serve to be beneficial when considered in parallel to the existing representation of the Biopsychosocial Model’s application.

Regardless of the model of intervention that is selected by the evaluating therapist to initiate the assessment and intervention process, the most crucial element of the therapist's decision making should be focused upon occupation. In this, that the means by which intervention is delivered is focused upon occupation as an actionable task of daily doing, and that it is meaningful and purposeful to the lived experience and need for desired outcomes within the individual.

Other options for appropriate models of occupation that can be utilized in the creation of individualized clinical care plans include (Turpin & Iwama, 2011):

-

Occupational Performance Model (AUSTRALIA) (OPMA)

-

Occupational Adaptation (OA)

-

Person—Environment—Occupation—Performance (PEOP) Model

-

Person—Environment—Occupation (PEO) Model of Occupational Performance

-

Ecology of Human Performance

-

Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E) as a component of the larger text entitled Enabling Occupation II (EO-II)

-

Model of Human Occupation (MOHO)

-

Kawa Model

* The included PDF offers an expanded articulation of the use of each model.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY IN THE PROMOTION OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

In the previous sections of OT For Women's Health, an elaborated articulation of Scaffa, Reitz, and Pizzi’s (2010) insights to the application of occupational therapy philosophy and practice to the service of community-based interventions is provided. Moving the professional focus away from the individualized level of care towards a one that addresses public health needs by way of family, community, and societal levels of intervention is a movement that has been shifting within the paradigm of the OT profession (Scaffa, Reitz, & Pizzi, 2010). Early detection and prevention remain primary, while any combination of health services, health promotion, and health protection strategies can be utilized to effectively accomplish these objectives (Scaffa, Reitz, & Pizzi, 2010).

Below, Table 2 depicts a situational analysis of the authors recommended components of how to organize information for community health interventions when considering their application to the specific population of women who have experienced sexual assault and as a result have been living with PTSD.

Table 2.

Situational Analysis Component and the Application to Sexual Assault and

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD):

A general description of the population, including health behaviors, disease, injury, and disability incidence and prevalence statistics.

-

1:6 women in the United States will be the victim of an attempted or completed rape during her lifetime, how does this statistic compare to the community prevalence?

-

Most assaults are committed by someone that the victim knows

-

Research indicates a strong correlation of sexual assault with the diagnoses of depression, anxiety, PTSD and pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD)

-

PTSD is twice as a common to be diagnosed in women than in men

-

Internalized shame and guilt keep many women from coming forward about their traumas and seeking appropriate intervention

An environmental scan to identify environmental enablers and barriers.

-

What percentage of the female population has access to healthcare coverage? How is it being utilized?

-

Are there clinics and/or programs in the community that specifically aide sexual assault survivors?

-

Are gynecological and/or urological clinics screening women with complaints of PFD for a history of sexual trauma?

-

What is the correlated rate of referral for mental health services by providers diagnosing or treating PFD?

-

What is the correlated rate of referral to pelvic health clinics by mental health providers treating patients with a history of sexual trauma?

-

Are there any pelvic health rehabilitation therapists practicing within the community?

Interviews with stakeholders to ascertain community goals related to health and occupation.

Collaborate with…

-

Obstetrics and Gynecological clinics

-

Urogynecological clinics

-

Urological clinics

-

Psychological/Psychiatric clinics

-

Sexual assault programs

-

Community hospitals

-

College/university campuses

… to determine service goals and gaps in provisions of care that elicit positive impact to client populations served.

Measures of health status and intrinsic factors to determine the constraints and capabilities for occupational performance.

-

Quantitative data extraction to determine frequency and severity of correlated diagnoses such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety through screening tools within the community (e.g., Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale, Severity Measure for Depression—Adult [adapted from the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9)], and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 [PCL-5])

-

Use of survey to generate qualitative data inventory to determine perceptions of occupational impact upon the population of female survivors of sexual assault.

Measures of occupational participation and community engagement.

-

How are existing programs within the community being accessed and utilized?

-

What methods of advertising reach the greatest number of potential women in need (e.g., social media platforms, web-based advertising, doctor office pamphlets, direct inquiry to healthcare professionals)?

-

Collect quantitative/qualitative data regarding perceived needs and interests for occupational resources/outlets or programs that may be implemented.

(adapted from Scaffa, Reitz, & Pizzi, 2010, p. 216)

The desired outcomes of occupational therapy intervention at the community level are congruent with the objectives for outcomes at the individualized level of care. As outlined within the OTPF, the primary objectives of occupational intervention are to achieve health and wellness; prevention of injury, disease, and disability; occupational performance; role competence; adaptation; client satisfaction; and quality of life (AOTA, 2014; Scaffa, Reitz, & Pizzi, 2010). To achieve these outcomes, intervention may potentially include one or more of the following approaches: create, promote, prevent, educate, consult, compensate, adapt, modify, maintain, remediate, restore, and establish (Scaffa, Reitz, & Pizzi, 2010).

CONCLUSION

The incidence of sexual assault perpetrated against women in the United States is alarmingly high. As the female brain has unique and distinct neurochemistry, research has shown that their propensity towards the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is twofold that of their male counterparts, despite men being subjected to traumatic scenarios at a greater rate. While prevention is the best course of action for reducing the number of females living with the experience of PTSD resulting from sexual trauma, there remains a present need for better addressing the lived experience and perceived quality of life (QOL) that is grossly impacted by the ongoing experiences of this population.

The occupational therapist (OT), particularly the trauma-informed therapist specializing in the practice of pelvic floor rehabilitation, has a unique combination of skills to address the multifaceted needs of the survivor from a biopsychosocial landscape. Research indicates that addressing both the physical and mental components of such trauma are paramount in the effective recovery of the experience. Through restorative biomechanical approaches, the adapting of routines, educating and encouraging the use of coping strategies and compensatory skills, and directly facilitating engagement in meaningful, purposeful tasks, the profession of occupational therapy has much to offer the female trauma survivor in her quest for wellness and improved QOL. OTs can make an enormous difference in the lived experiences of these women through the creation of individualized and community level programs to facilitate positive outcomes.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

IF YOU HAVE EXPERIENCED A TRAUMA:

- GET IMMEDIATE HELP-

If you are in crisis and need immediate support or intervention, call, or go the website of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255). Trained crisis workers are available to talk 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Your confidential and toll-free call goes to the nearest crisis center in the Lifeline national network. These centers provide crisis counseling and mental health referrals. If the situation is potentially life-threatening, call 911 or go to a hospital emergency room.

- FIND A HEALTHCARE PROVIDER OR TREATMENT -

For general information on mental health and to locate treatment services in your area, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Treatment Referral Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357). SAMHSA also has a Behavioral Health Treatment Locator on its website that can be searched by location.

FOR THE OT SEEKING INFORMATION ON BECOMING A PELVIC FLOOR THERAPIST:

RECOMMENDED BOOK LIST:

-

In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness - Peter A. Levine

-

Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma - Peter A. Levine

-

The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma Treatment (Norton Professional Book) - Babette Rothschild

-

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma - Besel van der Kolk

-

Overcoming Trauma Through Yoga: Reclaiming Your Body - David Emerson

REFERENCES

Abajobir, A. A., Kisely, S., Maravilla, J. C., Williams, G., & Najman, J. M. (2017). Practical strategies: Gender differences in the association between childhood sexual abuse and risky sexual behaviours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 249–260. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.023

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2012). Occupational therapy practice guidelines for adults with serious mental illness. Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2014). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (3rd ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(Suppl. 1), S1-S48.

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2015). Fact sheet: Occupational therapy’s role with posttraumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/AboutOT/Professionals/WhatIsOT/MH/Facts/PTSD%20fact%20sheet.pdf

American Occupational Therapy Association. (2018). AOTA’s societal statement on stress, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(Suppl. 2), 7212410080. https://doi. org/10.5014/ajot.2018.72S208

American Psychiatric Association. (2010). Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/acutestressdisorderptsd.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ptsd- guideline/ptsd.pdf

Carreiro, A. V., Micelli, L. P., Sousa, M. H., Bahamondes, L., & Fernandes, A. (2016). Clinical article: Sexual dysfunction risk and quality of life among women with a history of sexual abuse. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 134, 260–263. https://doi- org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.01.024

Florian, P. M. (2018). The unwelcome guest. Working with childhood sexual abuse survivors in reproductive health care. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 45, 549–562. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.ogc.2018.04.009

Gentry, K., Snyder, K., Barstow, B., & Hamson-Utley, J. (2018). The biopsychosocial model: Application to occupational therapy practice. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy: Vol. 6: Iss. 4, Article 12. Available at: hDps://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1412

Gerney, A., & Muffly, A. (2015). Sexual assault: Building the evidence for occupational therapy...AOTA/NBCOT National Student Conclave, Dearborn, Michigan, November 18-19, 2016. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 69, 1181–1185. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2015.69S1-PO2086

Gottfried, R., Lev-Wiesel, R., Hallak, M., & Lang-Franco, N. (2015). Inter-relationships between sexual abuse, female sexual function and childbirth. Midwifery, 31, 1087–1095. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.midw.2015.07.011

Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute. (2019). Continuing Education, Pelvic Floor Level 1. Retrieved from https://hermanwallace.com/continuing-education-courses

Inslicht, S. S., Metzler, T. J., Garcia, N. M., Pineles, S. L., Milad, M. R., Orr, S. P., … Neylan, T. C. (2013). Sex differences in fear conditioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(1), 64–71. https://doi-org.prx- usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.027

Kim, Y.-K., Amidfar, M., & Won, E. (2018). A review on inflammatory cytokine-induced alterations of the brain as potential neural biomarkers in post-traumatic stress disorder. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.06.008

Ney, L. J., Matthews, A., Bruno, R., & Felmingham, K. L. (2018). Modulation of the endocannabinoid system by sex hormones: Implications for posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. https://doi-org.prx- usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.07.006

Porges, S. W. (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. a polyvagal theory. Psychophysiology. 32, 301–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb01213.x

Porges, S. W. (1998). Love: an emergent property of the mammalian autonomic nervous system. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23, 837–861. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00057-2

Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42, 123–146. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(01)00162-3

Porges, S. W. (2003). The Polyvagal Theory: phylogenetic contributions to social behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 79, 503–513. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00156-2

Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74, 116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009

Porges, S. W. (2009). The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 76, S86–S90. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.17

Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. 1st Edn. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Postma, R., Bicanic, I., van der Vaart, H., & Laan, E. (2013). ORIGINAL RESEARCH-WOMEN’S SEXUAL HEALTH: Pelvic floor muscle problems mediate sexual problems in young adult rape victims. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10, 1978–1987. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1111/jsm.12196

Ramikie, T. S., & Ressler, K. J. (2018). Mechanisms of sex differences in fear and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 83(10), 876–885. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.016

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network [RAINN]. (2018). Scope of the problem: Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.rainn.org/statistics/scope-problem

Ryan, G. L., Mengeling, M. A., Summers, K. M., Booth, B. M., Torner, J. C., Syrop, C. H., & Sadler, A. G. (2016). Original Research: Hysterectomy risk in premenopausal-aged military veterans: associations with sexual assault and gynecologic symptoms. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 214, 352.e1-352.e13. https://doi-org.prx-usa.lirn.net/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.003

Scaffa, M. E., Reitz, S. M., & Pizzi, M. A. (2010). Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and wellness. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company.

Turpin, M. & Iwama, M. (2011). Using occupational therapy models in practice: A field guide. [e-book]. Churchill Livingstone.